登录后获得更多功能

您需要 登录 才可以下载或查看,没有账号?注册

x

http://www.bikeradar.com/fitness ... back-for-good-20115

By Nick Morgan

Whether you’re injured, on holiday or just feeling lazy, losing fitness is something all riders dread. You’ll lose less form and come back stronger if you follow this advice.

When Lance Armstrong announced he would be returning to professional cycling in 2009, many non-cyclists assumed this meant the result of the 2009 Tour de France was a foregone conclusion. The seven-times winner would simply dust down his Trek, pull on his Nikes and start winning again.

There is a chance this might actually happen, but as anyone who’s had any time off from regular cycling knows, no matter who you are, returning from even a relatively short lay off from bike racing, long-distance touring or even commuting isn’t easy.

Armstrong hasn’t been idle for the past three years – a couple of marathons and, more recently, mountain bike and cyclo-cross races will have kept him in pretty good shape – but even an athlete of his quality will have succumbed to something most cyclists dread.

Detraining

Detraining is what the term pretty much implies – the loss of fitness that occurs during a period of inactivity or reduced training. Whether you’re injured or simply taking a break from riding, not being on your bike will have a negative effect on your cycling. To a certain extent it’s not as bad as it initially sounds, as the common perception is that fitness losses can be almost immediate and take months of hard training to win back. The truth is more complex and perhaps slightly less disastrous than most cyclists believe.

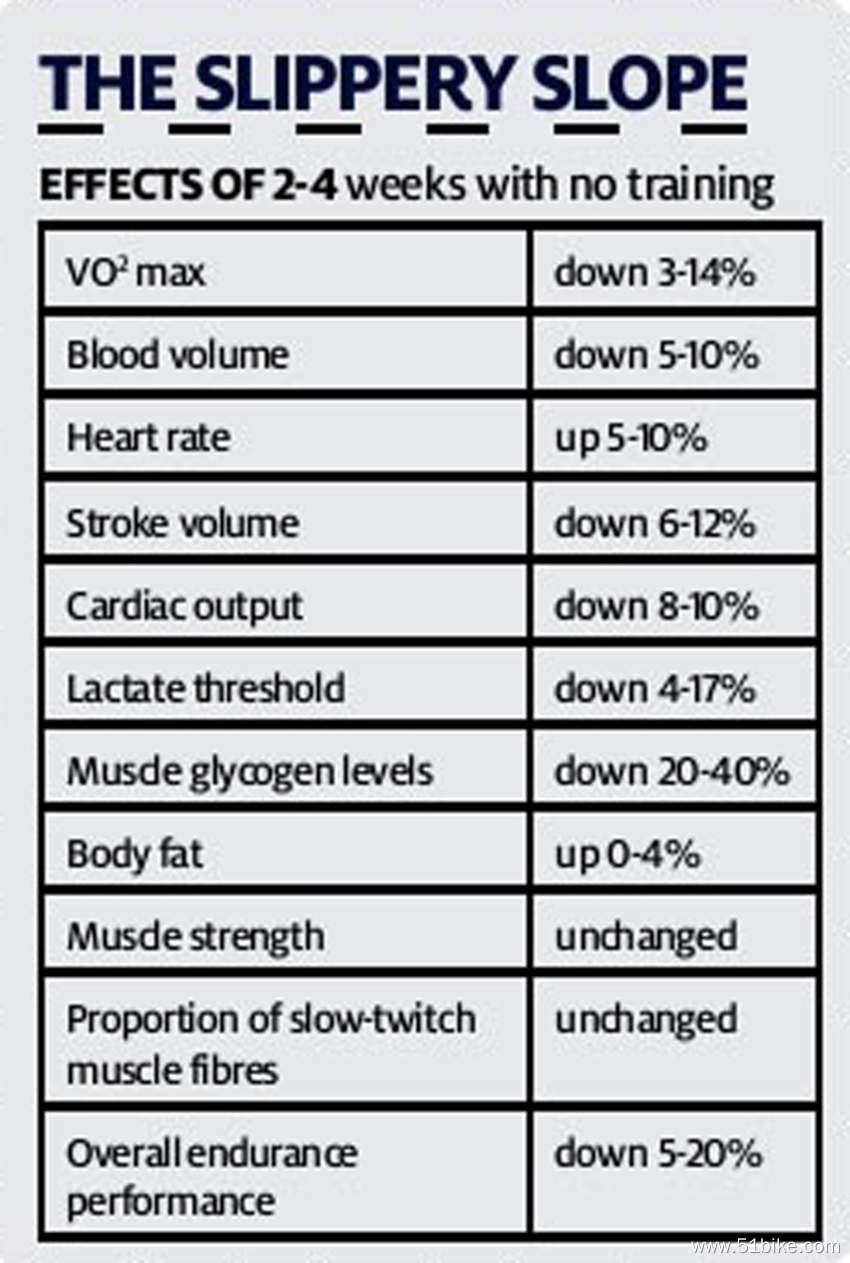

As the 'slippery slope’ table below indicates, a sustained bout of inactivity can result in significant detraining effects in a variety of areas. But knowing what to do during an inactive period and how to approach your comeback can dramatically reduce these losses. First, though, you need to understand exactly what happens to your body when you stop getting on the bike every day.

The slippery slope: the slippery slope

What happens when you stop training?

The severity of the detraining effect depends on the length of time you spend away from the bike. Two or three days should have little impact and may even result in slight improvements as your body recovers from hard training.

However, a host of studies have shown that once you go beyond a few days, the benefits of recovery are outweighed by the loss of fitness. The cardiovascular system, so crucial for endurance athletes, is one of the first to be affected. The central reason for this is that blood volume is reduced. Though your heart rate will increase during any exercise you can manage, it doesn’t do so by enough to compensate. This means your overall cardiac output goes down and your maximal oxygen capacity (VO2 max) – arguably the most crucial measure of endurance fitness – also decreases.

“From the many studies that have been done it seems that VO2 max in well trained athletes declines in a roughly linear fashion from around four percent in the first week or two to around 20 percent after eight weeks,” says Iñigo Mujika, who has written several papers on detraining and has worked with five times Tour de France champ Miguel Indurain, among others. “Afterwards it stabilises at this lower level, which is generally still higher than in sedentary individuals.”

Metabolic downturns can also occur quite quickly. Glycogen is the key here as it’s the primary fuel source for exercise. By ceasing to train, you attack your metabolism from two sides. Firstly the body stops becoming so effective at converting glucose to glycogen; indeed, a study at Odense University, Denmark, showed muscle glycogen concentration decreased by 20 percent after just four weeks of inactivity in trained triathletes.

Secondly, training teaches the body to spare glycogen by burning fat instead, but ceasing training reverses this process meaning a greater percentage of glycogen is used at every stage during exercise, so you run out faster. “The glycogen concentration in trained muscles declines very rapidly, reverting to sedentary values within a few weeks of training cessation,” says Mujika.

There is some good news though. At the muscular level things take a little longer to go wrong. Capilliarisation – the process by which capilliaries wrap themselves around the muscles to provide greater oxygen transport and hence greater exercise efficiency – has shown to be unaffected by a short period of detraining in several studies (though others have registered a small decline).

Furthermore, muscle fibre distribution remains unchanged for the first few weeks after stopping. It takes up to eight weeks for the slow-twitch fibres – so important for endurance athletes – to start to convert to fast-twitch. Also, studies have shown that strength gains are largely retained for about four weeks with no training.

Overall though, performance undoubtedly suffers quite quickly. Studies looking at time-to-exhaustion tests have registered a 9.2 percent overall performance decline after two weeks of inactivity, rising to 21 percent and 23.8 percent after four and five weeks off respectively. So, if you sense an injury coming on, it may be best to take a week off immediately rather than push on and risk a long lay-off further down the line.

“Endurance-trained athletes should avoid detraining periods longer than a few weeks,” explains Dr Cyril Petibois from the University of Bordeaux, who studied the detraining effect on competitive rowers. “This is because alterations of the metabolic adaptations to training may become rapidly chronic after such a delay.”

Do age, sex or prior fitness make a difference?

It’s clear from research that, contrary to expectations, seasoned athletes actually lose fitness faster than those who have only recently started exercise programmes. Studies show that VO2 max decrease in well trained individuals over two to four weeks of detraining is four to 14 percent, whereas for less well trained individuals it’s only three to six percent. However, it should also be noted that following longer lay-offs, well trained athletes still retain physiological levels well above sedentary individuals whereas fitness gains in cyclists who only recently took up the sport will be completely lost.

Interestingly though, while prior fitness level has a big impact on the detraining effect, age and gender seem to have far less. One study at Akdeniz University in Turkey did find a positive relationship between age and detraining decline, but it only looked at men over the age of 60, and researchers at the University of Maryland found that there was no significant difference in the detraining effect of young (20-30) men, young women or old (65-75) men. Only older women registered significantly worse fitness losses.

How to combat detraining

Your most useful weapon in the battle against detraining can be summed up in one word: intensity. All the studies that have examined detraining have found that fitness losses can be minimised if you can keep the intensity of your training going, even if you have to drastically cut the volume.

“Maintenance of training intensity is the key factor in retaining training-induced physiological and performance adaptions during periods of reduced training, whereas training volume can be reduced by around 60 to 90 percent without having a huge effect,” says Mujika.

So, if you fancy a holiday from the slog of base training then a few weeks of less mileage is fine so long as you do high-intensity short rides to compensate. You won’t get fitter, but you shouldn’t lose too much and it might leave you refreshed for another bout of hard training where more gains can be won. Crucially however, according to Mujika, though it’s fine to decrease volume, you should take care not to decrease training frequency by more than 20 to 30 percent.

But it gets trickier if injury prevents cycling of any kind, in which case you need to get the intensity from somewhere else. Presuming that if you can’t ride you’re unlikely to be able to run or use any other kind of cardiovascular gym equipment, your best bet is to turn to swimming.

Several studies have shown that in moderately- trained individuals, cross-training of this sort can reduce the cardiovascular and metabolic losses of detraining. And though you’re in the pool rather than on your bike, intensity is still the key. So regardless of your level of swimming, try to do fast repetitions as often as you can rather than just steady swimming, as this should retain your fitness levels far better.

An epic comeback: an epic comeback

Starting back

Getting your comeback schedule right is crucial. Despite the severity of the detraining declines, they can be completely reversed relatively quickly.

Scientists at San Diego State University studied an elite female cyclist returning after five weeks out with a broken collarbone. They found that the majority of her physiological variables were completely restored within six weeks of retraining. But it’s imperative to recognise that because some aspects of fitness decline faster than others your returning-to-cycling schedule requires a slightly different balance from a regular routine.

For example, because strength gains are not as affected as cardiovascular and metabolic adaptions, it’s the latter that you need to work on first and foremost. So any lower body gym work that may form a very justified part of your regular schedule should be reduced to the periphery on your comeback.

Likewise, a study by a team of Norwegian researchers has shown that the fastest way to improve your VO2 max and overall endurance performance is to do shortish bouts of intensity work that are at a speed significantly faster than you would ride generally, but not so fast that they leave you exhausted for the next session. This way a relatively large part of your weekly training routine can be done at an intensity greater than that of a steady ride.

“Training volume is not a substitute for training intensity,” says Professor Jan Helgerud from the Norwegian team. “You should try to fit as many intensity sessions into your week as possible, but to do this they needn’t be done at full speed.”

Eight-week programme

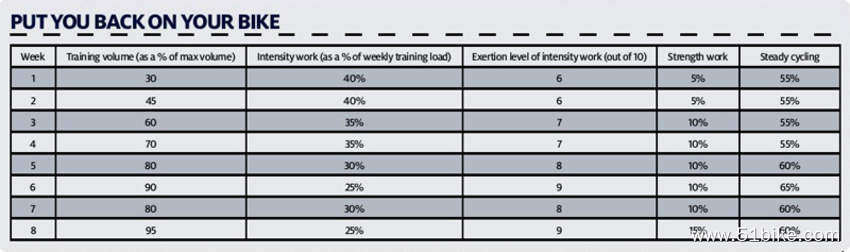

The ‘Put you back on your bike’ table, below, should provide a good guide to an eight-week retraining programme, though it requires a little explanation.

Put you back on your bike:

The second column – training volume – means that if you would ride 300km on your maximum training week of the year, then on your first week back you should aim for 30 percent of this (ie, 90km). The third, fifth and sixth columns indicate the ideal make-up of your week. So week one should consist of 55 percent steady riding, 40 percent intensity work and five percent strength. Note that this presumes that any injury is completely recovered and therefore intensity work will not aggravate it.

Of course, if you have an injury that only permits steady riding then that’s all you should do. Note also that the intensity percentage starts quite high – this is so that you start attacking those cardiovascular losses immediately. But it’s also the point of the fourth column – exertion level. Because you’re doing a lot of intensity work such as intervals and repetitions, you shouldn’t do them flat out or you’ll be totally exhausted and very likely to get injured again. So the fourth column provides a perceived exertion guide for the intensity work.

This schedule is ideal for someone returning from injury in mid-season and focuses on recovering lost fitness as fast as possible. The emphasis may be different if competition is still months away; in that scenario you may wish to build up a base of more steady riding first. Either way, a sensible comeback is likely to yield great results. We bet Lance has been sensible!

|